The Real Flex: Reimagining the Medical Education of the Negro

Re-imagining who can aspire to be a doctor.

This article written by Khalid Smith, MedReimagined cofounder was originally published in Word In Black and can be found here

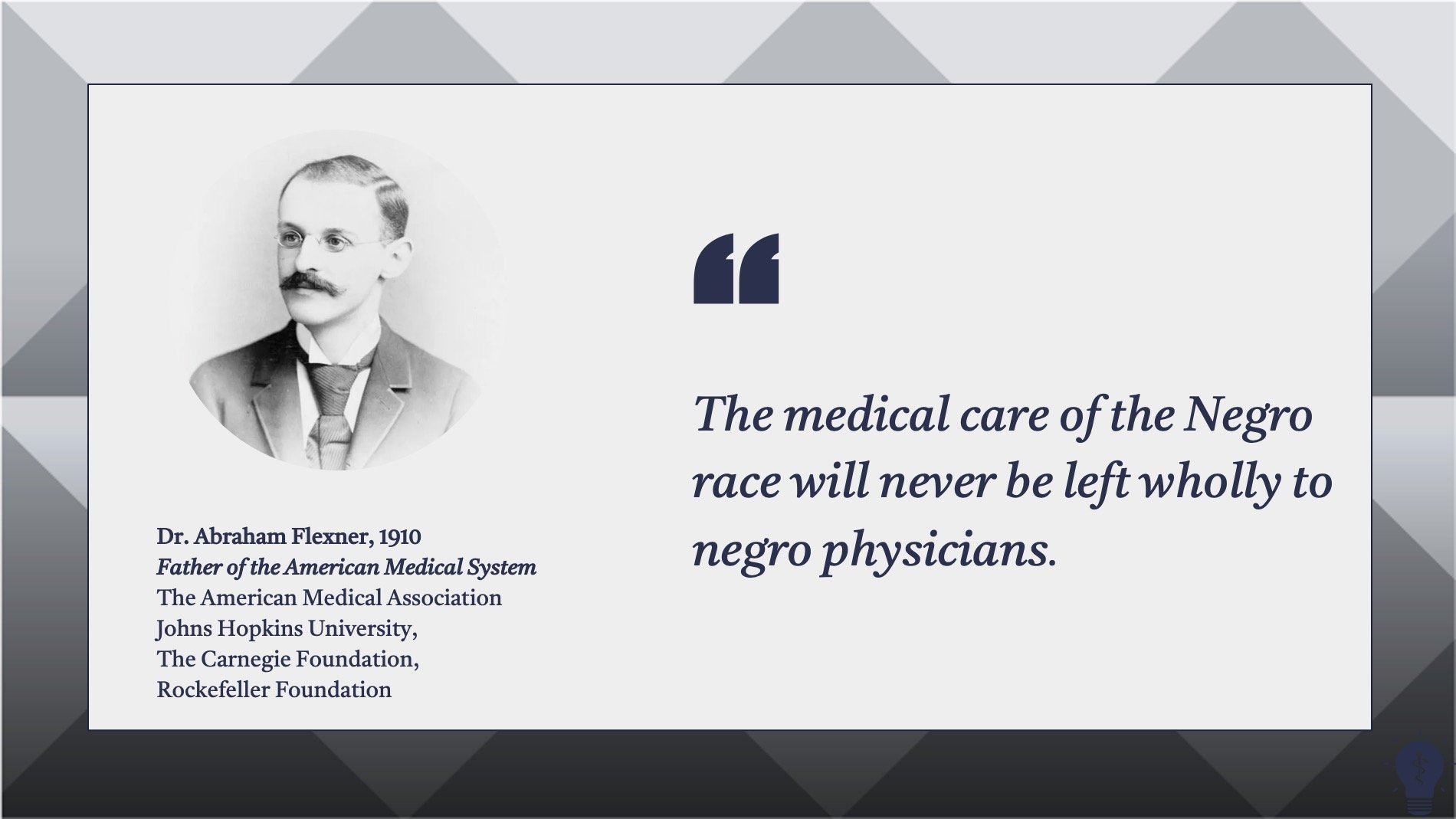

As 2022 closes, two cases aimed at preventing medical schools from using race as part of a holistic admission process sit before the Supreme Court. Six conservative judges will likely decide the outcome but everyone that loves life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness should care that, “the medical care of the negro race will never be left wholly to negro physicians.”

He said "never" in 1910. You laugh. But we're in front of the supreme court fighting in 2023.

No, that quote is not (yet) an opinion handed down from six conservative judges. It’s actually the opening sentence of the chapter entitled “The Medical Education of the Negro” from a 1910 landmark publication, “Medical Education in the United States and Canada.”

To be sure, every piece of hundred-year-old racist rhetoric can’t be directly connected to today’s challenges. But this isn’t just any text.

The Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, the John D. Rockefeller foundation, the American Medical Association, and Johns Hopkins University came together at the turn of the last century to focus on elevating the poor state of healthcare in America.

Their first step was to send a former teacher and author named Abraham Flexner to visit all 155 medical schools in the U.S. and Canada and propose how to improve them. Fueled by huge financial commitments from the Carnegie and Rockefeller foundations, the Flexner report’s recommendations were enshrined in law across all 50 states and became the foundational blueprint of the modern American medical system

In the 112 years since, America has become a world leader in medical research, and in training physicians. But, at the same time, there has been a consistent shortage of Black physicians, and the Black community finds itself dependent on others for care. Care that has left the Black community lagging behind our white counterparts in nearly every measurable health outcome — and America, overall, ranking last among developed nations in healthcare.

The US kind of sucks at spending money to get healthier

In this age of outright denial, the Flexner report stands as a rare instance where systemic racism’s invisible hand wrote out receipts.

Reimagining Originalism:

Justice Ketanji Brown-Jackson, in her short time on the bench, has shown that she may literally be the Black Justice we’ve needed since Thurgood. She’s dismantled flimsy originalist arguments again and again and again.

Her central thesis is that the framers of the 14th amendment redesigned the Constitution in an explicitly race-conscious way — and therefore, it’s not unconstitutional for the very remedies the amendment was put in place to protect to be race-conscious.

Over 40 organizations led by the Association of American Medical Colleges have already compiled an unparalleled amount of expertise into an amicus brief summarizing “a decades-long overwhelming body of scientific research showing that diversity literally saves lives.”

Their grasp of the research is impeccable. But I think they missed a larger point, one that needs to be made because Black communities across America are sick and tired of being sick — and dying.

We have the right to life. It is our right to demand the American medical system produce doctors qualified to provide us with the best care.

We have the right to liberty. It is our right as a community to choose whom we will trust with our health care.

We have the right to pursue happiness. State policies that restrict qualified Black candidates from pursuing training in one of the most lucrative and ubiquitous professions perpetuate the lower socio-economic status of Black communities.

Black communities across America are sick and tired of being sick — and dying.

The Black community has too long been denied these rights — more so, the current medical system has, in fact, been designed to deny the Black community these rights.

We have the right to remedy this. We have been doing so. That is who we are. Those that wish to see us continue to die are attempting to thwart our progress. But do not mistake laboring in the face of injustice with accepting it. The original intent, past history, and current incarnation of the laws that established the rules and requirements for becoming a doctor were and are deeply racist.

Not considering race in a reimagining of the pathway to becoming a physician is actually denying Black, Latinx, and Native American communities their constitutional rights to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness protected by the 14th amendment.

Do we have receipts for such audacious claims? As a matter of fact, we do.

Receipt #1: The American Medical System was designed to produce inadequate numbers of physicians qualified to serve Black citizens.

40 yrs post slavery, northern trained Black MDs started medical schools in the rural south. Flexner shut them down.

Closing 5 Medical Colleges dedicated to training Black physicians for still largely rural and poor Black communities rather than calling for investment in these schools has been shown to have contributed to a present-day gap of 35,000 practicing Black doctors, eerily close to the current number of 55,000 missing black physicians based on population percentages.

Flexner didn’t attempt to argue that two institutions might train physicians to serve 10 million Black citizens while 60 would be required to serve 60 million white citizens. Black physicians were to be few, and their preparation less comprehensive than their white counterparts. True to Flexner’s design, between 1910 and 2008, Black physicians remained less than 2.5% of U.S. physicians.

Receipt #2: Integration was not intended to be a solution, and predominantly white institutions have failed at training white or Black doctors to serve Black populations.

Most African-Americans that become doctors choose general practice vs the more lucrative specialties.

Flexner explicitly made the case for integration as a rationale for closing the women’s medical colleges but not in the case of the historically black ones.

Fourteen new medical schools were accredited between 2014 and 2019. Most cite diversity’s role in health equity needs as part of their charter. Despite this, their total 2019 enrollment was only 8% Black — far short of the 13% Black people make up of the population and shorter still than the amount needed to close the current gap of 55,000 missing Black physicians.

Research has proven education with diverse peers facilitates more meaningful cross-cultural learning, and medical students who are educated in a diverse student body are better able to work with patients from diverse backgrounds.

Receipt #3: The American Medical System was designed to value the protection of white lives and health over Black lives and health.

Bruh, I am NOT making this up! Go read the report for yourself!

With deliberately inadequate numbers of physicians qualified to care for us, Black populations consume 20% fewer physician services than their white peers.

Researchers characterize this discrepancy as a problem of access to care with underlying causes of lack of insurance, lack of reliable transportation, or higher levels of mistrust in the medical system. However, a cursory reading of the Flexner report reveals analogies to long voter lines, and other forms of voter suppression.

The intentional design of an insufficient system leads to underutilization that makes it easy to label the disenfranchised — Black people — as disinterested.

Receipt #4: The American Medical System was designed to advantage white wealthy aspirants to become doctors and discourage poorer, Black, or rural aspirants.

Flexner: “The sole reason for a preliminary requirement of any kind is as a method of restricting the study of medicine to those in whose favor an initial presumption of fitness exists… Every competent and earnest instructor is seriously hampered by the vain effort to aid those who are beyond human help.”

The legacy of Flexner — and its philanthropic support for its legislative agenda — was establishing state boards that controlled licensure and accreditation over institutions, but also had the power to establish prerequisites for admission to medical school.

Making medical careers exclusive was about deciding who to exclude, and the way they did that was by biasing prerequisites toward who they deemed worthy of studying medicine in the first place.

Med school prerequisites have been criticized for being impediments to equity and for not being a strong gauge of candidate performance once admitted to medical school.

Class rank, grade point average (GPA), Medical College Admissions Test (MCAT) scores, requirements of healthcare experience, and the interview process have all been shown to be areas where bias is not just present but designed into the system. The very lawsuit that purports strict adherence to the current system, without any consideration for race, is, in fact, holding up a system designed to exclude on the basis of race and socioeconomics — but disguised as “merit.”

Flexner paints Black Americans as unworthy of care, limited in our ability to care for ourselves, inconsequential to the overall health of America, and incapable of creating our own institutions and solutions. While the system he built perpetuates this myth, this is not our story.

But still we rise.

Flexner closed our schools, but new medical schools are building the capacity we need.

In 2024 Morgan State University in Baltimore and Xavier University in New Orleans plan to open only the fifth and sixth medical schools at historically Black colleges. At the same time, Morehouse Medical College is partnering with large hospital networks to create regional medical campuses located in high-need areas and double their class size over the next five years. These experiments are important because HBCUs are consistently showing that they can “shift the curve” by changing the profile of the student admitted to medical school and then proving with data that their graduates are as or more effective than students admitted with a different set of standards.

Medical schools are increasingly admitting candidates that look like the communities they serve.

Flexner said making the medical field exclusive meant choosing whom to exclude. But medical schools are increasingly using holistic review to produce medical school enrollments that are reflective of the populations they serve.

Foundations are recognizing their complicity and making amends.

The same American Medical Association that underwrote the Flexner report is now a signee of the amicus brief opposing this recent suit. It may be a long wait for the Carnegie and Rockefeller foundations to put the same support behind remedying Flexner’s legacy as they did creating it. But organizations like Bloomberg Philanthropy’s Greenwood Initiative are putting $100 million behind making medical school debt-free for qualified minorities. And, groups like Salud Education are putting $110 million into building for-profit medical schools when states fail to distribute a fair share of funding to their minority-serving institutions.

Even conservatives, reluctantly, agree.

Even those that would defend America’s last-place ranking in health outcomes among wealthy nations agree that the root of the problem is that America is bigger, more diverse, more litigious, and “unfortunately” has disparities driven by higher levels of poverty. Their solution is to “Do all we can to reduce cost without jeopardizing the high quality of care” (the rest of America gets).

We agree. Focusing on equity to improve the number of Black doctors produced by the system as a whole does not sacrifice quality of care. It follows all the medical research, empowers experts, addresses issues of persistent poverty, addresses our doctor shortage, improves the economy, increases the collective cultural competency of the physician workforce, reduces litigation from mistrust, and makes Americans live longer. I can’t see any drawbacks unless, of course, the supreme court is going to say that the original originalism is correct and “the medical care of the negro race will never be left wholly to negro physicians.”